According to Vikentiy Khvoyka’s research, the territory of Protasiv Yar was once the site of a prehistoric hunting settlement. These slopes still remember the time when ancient people chased and finished off mammoths here.

At the end of the 19th century, as the Pechersk Fortress expanded, residents of Pechersk were resettled to this area. Quickly switching into business mode, they bought pasture lands from the village of Sovky and began construction and farming. After World War II, locals and employees of the Sugar Beet Institute reinforced the slopes and planted orchards. In 1966, the ravine was granted the status of a public recreation park.

In 2001, the city government laid a road through the ravine. At first glance, it seemed like a reasonable initiative – but part of the land was suddenly transferred into private ownership, with a new «intended use». Later, another 4 hectares were handed over to a company called Protasiv Yar LLC. When the lease expired, the land was returned to the city – but somehow, it was then mysteriously passed into sublease again.

On April 26, 2007, the Kyiv City Council illegally leased 3.23 hectares of land in Protasiv Yar.

On June 6, 2018, one year after the lease had expired, a new sublease agreement was signed between Bora LLC and Dayton Group LLC – the latter owned by oligarch Hennadii Korban. The deal was also illegal.

The beneficiaries of these schemes (surprise!) once again included Hennadii Korban, his business partner Oleh Levin, and Kyiv businessman Ihor Kucherenko – a figure linked to past organized crime networks.

And thus began the long war for Protasiv Yar.

On June 16, 2019, Roman Ratushnyi and his neighbors filed a lawsuit in Kyiv’s District Administrative Court, demanding the cancellation of an illegal construction permit issued to Dayton Group LLC. And they won.

But that victory came at a price.

Throughout May and June 2019, residents of Protasiv Yar were attacked. The police did not protect the protestors or the local community.

Roma wasn’t surprised – he had never trusted the police. Or more precisely, he had never trusted the cops.

* * *

2011. Night. Solomianskyi district.

A drunken brawl. Possibly an attempted murder. Very close by. Roma and Zakrevska witnessed it by chance.

«Zhenya, don’t», Roma said. «You can’t call the cops. You never call the cops. Don’t you know that? They won’t help. It’ll only get worse.»

He was maybe fourteen at the time. Still a kid – or maybe already not?

Zakrevska had never harbored illusions about law enforcement. But even she was taken aback by how firmly this fourteen-year-old had internalized that truth.

And, as it turned out, he was always right.

* * *

June 24, 2019, 2:00 PM

Roman Ratushnyi receives a direct threat from one of the security chiefs at the illegal construction site in Protasiv Yar. In the presence of a National Police officer, the guard says:

«I’ll find you and break your spine.»

This same man had already attacked Roman once before.

* * *

Roma hurls his phone against the wall.

His mother watches with stoic sadness – the phone was expensive. The meeting about Protasiv had clearly gone poorly.

Roma believed in people. He had a talent for seeing where someone could shine – and would gently nudge them toward work that suited them. But sometimes, his way of communicating was too complex for the broader community – filled with literary allusions, international legal practice, and historical context. His mother would gently hint that simpler words might help, but Roma didn’t budge. He’d spend hours explaining, mediating conflicts, offering coffee, and holding everyone together in the same common cause – defending Protasiv.

But sometimes he’d come home after a long day of endless meetings, exhausted and furious, barely holding back tears. Calm and composed in public, at home he would explode – pacing the room, swearing, throwing things, choking on frustration.

He couldn’t stand wasting hours in meetings where only 5% was constructive, and the rest was endless petty drama – the kind of circular «office politics meets village gossip» nonsense that killed any real progress. People needed constant guidance, encouragement, pressure.

And yet the next morning, he’d get up and do it all again.

Because he believed in the community he was forging with his own hands.

* * *

And the Knight Took No Silver

And the knight took no silver,

Nor did he cloak himself in silken robes.

No gold could tempt him, no bribe could bind him –

For no man can purchase,

With copper coin or gilded lie,

A heart made of true gold.

They came to buy him,

With flattery and threats,

With promises whispered from behind velvet curtains.

But he stood unbent,

Unshaken as an oak in the wind,

For the forest was in him,

And the truth walked beside him.

August 14, 2019.

Lawyer Andriy Smyrnov*, a representative of the developer, contacts Roman Ratushnyi. Roma agrees to the meeting. His goal is to clearly communicate the position of the Protasiv Yar community: there is no place for construction here. He offers the only acceptable option – that Oleg Levin and Hennadii Korban abandon their development plans entirely.

At the start of the meeting, Ratushnyi tries to clarify that this is not a personal conflict. The issue, he says, lies in the legal risks that were ignored as early as the audit phase. These miscalculations, he explains, made the construction project legally impossible from the outset.

Smyrnov listens – briefly – before shifting tone. He moves to pressure. Whether it was a «friendly warning» or a direct threat is a matter of perspective. But the message is clear: either «the boy» takes the money – $50,000 – or «the boy» ends up in the forest.

«If we don’t reach a compromise», Smyrnov says, «I’ll call Oleg (Levin) and tell him I didn’t get the job done – but I don’t want gunfire and all that.»

«I can be a constructive negotiator between you and the business side. But if we can’t find common ground – the thefts, the beatings, the blood – it all hurts reputations. And I don’t want to be part of that.»

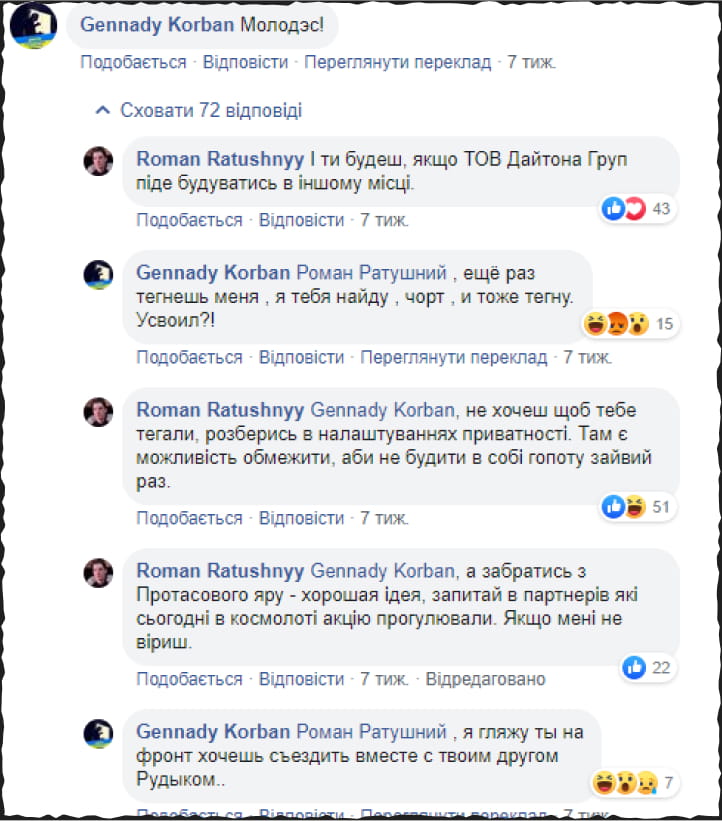

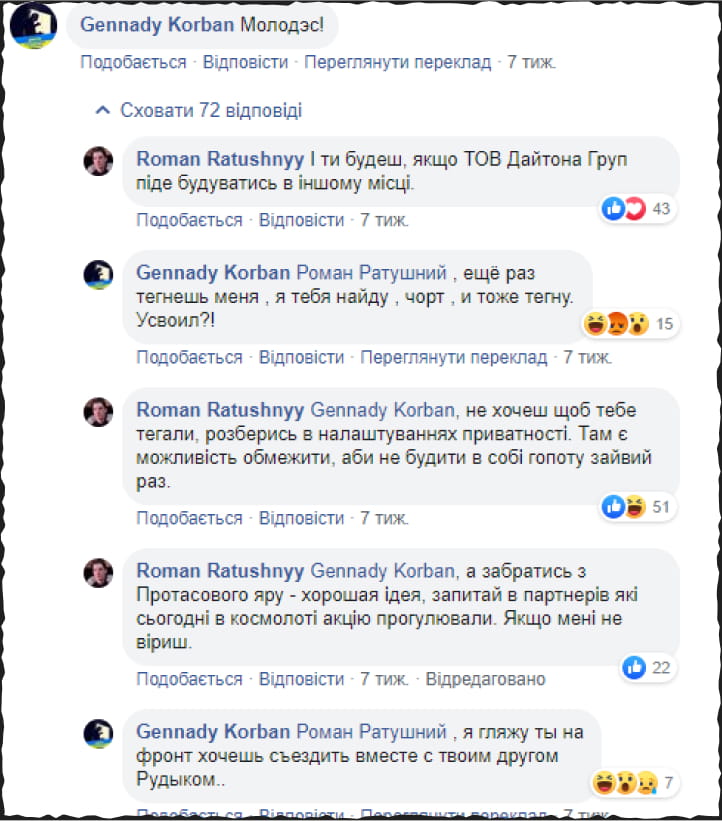

August 28, 2019. Hennadii Korban issues a threat to Roman Ratushnyi via Facebook.

Context: August 28, 2019. Public comments on Facebook under a post by Hennadii Korban, oligarch and business partner behind the controversial development project in Protasiv Yar.

Gennady Korban:

Bravo, well done! («Molodets!» – a patronizing or sarcastic «good job» in Russian.)

Roman Ratushnyi:

And you’ll be «well done» too – if Dayton Group LLC decides to build elsewhere.

Gennady Korban:

Roman Ratushnyi, if you tag me again – I’ll find you, you little shit, and I’ll tag you back. Got that?!

Roman Ratushnyi:

Gennady Korban, if you don’t want to be tagged – check your privacy settings. There’s a way to limit that. No need to awaken your inner thug again.

Roman Ratushnyi (next comment):

Also, Gennady Korban – leaving Protasiv Yar sounds like a good plan. Ask your partners who missed the protest action at the Cosmos cinema today. If you believe me, that is.

Gennady Korban:

Roman Ratushnyi, I see you’re aiming for the frontline. Want to go there with your friend Rudyk?

The threats were real. But the institutions were silent.

Every threat – every warning, every recorded insult, every message thick with violence – Ratushnyi and Zakrevska brought them to the Security Service of Ukraine and the Prosecutor General’s Office.

And the institutions... did nothing.

* * *

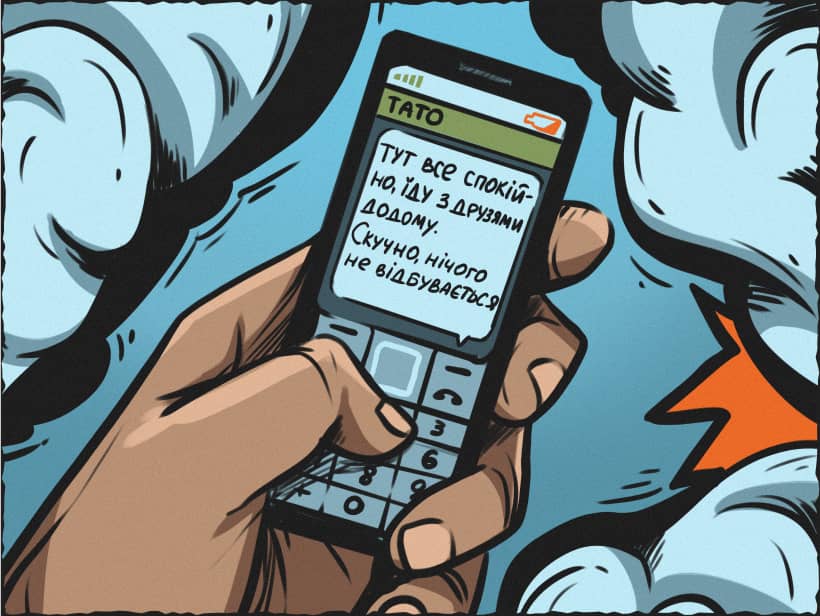

– Zhenya, hey, sorry it’s late. But the police just stopped me. They’re asking to check my backpack. And I have this very clear feeling I don’t have to let them. Am I right?

It was autumn. It was 2 a.m. Zhenya Zakrevska, half-asleep in a hotel room in Crimea, woken by the call. This was before all the Maidans, before the revolutions.

Still semiconscious, she tried to repeat what they’d discussed many times before. According to Article 11, Clause 6 of the Ukrainian Law on Police, officers could search a person or their belongings only if that person was officially detained – and only with a report, and two witnesses.

– Right... thanks, that makes sense. Can you tell them that? I’ll pass the phone. I mean, I’m just a teenager. When I say it, it doesn’t really land.

– Go ahead.

She heard him say, politely:

– Would you mind speaking to my lawyer?

And then she spoke:

– Good evening. Could you please tell me why he was stopped? Did he break any law?

– No, no, not at all. It’s just... someone was painting graffiti nearby, and then this young man showed up with a backpack. We just wanted to check. I’m pretty sure it’s not him. Polite guy, reasonable. Are you really his lawyer? If he just shows us what’s inside, we can all move on...

– I am. But I can’t ask him to do that. And you know you don’t have the legal right to insist. Yes, it’d be easier to open the bag. But the easy way isn’t always the right one. He knows his rights – and he’s right. Let’s not punish him for that.

A pause.

– Well… alright then. Have a good night, young man.

The officer handed back the phone.

– Thanks. Sorry for the trouble. Sleep well.

An hour later, another message.

– So what did you tell him?

– That kind of information costs a hundred bucks. And you call this a good night?!

* * *

September 15, 2019

One of the security guards at the Protasiv Yar construction site struck community coordinator Yuliia Kononenko in the head.

Diagnosis: concussion and a jaw injury.

The police refused to detain the attacker.

September 20

In front of witnesses, Dmytro Nikitin – head of site security – threatened Ratushnyi, Kononenko, Zakharchenko and their families with beatings and arson. He offered Roman money: name your price and walk away from the movement. Otherwise, he promised, Roman would «simply disappear». He mentioned torture. Ratushnyi recorded most of the conversation.

September 31

Roman was told: they were preparing to abduct him. Kill him. The cars started circling – black, low-slung, with strange plates. His official letter to President Zelenskyy changed nothing. Not a thing. The police ignored the criminal complaint, even after Korban’s threats. Roman changed his phone number. Moved out of his home.

* * *

– You quit smoking? Seriously? After all these years?

Zhenya automatically took the cigarette from his hand and, once again, scolded herself internally: how do I fall for this every time? Ratushnyi played it straight – and the more theatrical the audience, the more dramatic his monologue became.

– I’ve known her since she was thirteen. She smoked constantly. And now she quit? Sure. Let’s see how long that lasts.

In reality, Zakrevska never smoked at all. But back when Roman was a teenager, she had made a personal rule: she would never buy him cigarettes. He still smoked – just not with her help.

He protested. Called it ageism. Said they were friends, colleagues, equals. That she lacked empathy.

His strongest argument?

– You buy cigarettes for your clients in pre-trial detention! And for me – nothing!

Which was true. Defense attorneys in Ukraine often brought cigarettes to their clients – they were currency behind bars. But Roman took that as the ultimate injustice.

– Even prisoners get your cigarettes. But not me.

When he came of age and could buy them himself, he found a new form of protest.

Whenever a group went out for a smoke, and Zhenya happened to join in, he’d quietly offer her one – with the same casual gesture he extended to everyone.

He never lit it.

Because revenge, in Roman’s version, was always served cold. And unlit.

* * *

At first, Zhenya Zakrevska suggested that Roma leave the country – or at least relocate to another city – to reduce the risk of a physical attack. But it soon became clear: even in another city, there were no guarantees of safety.

In the end, Roma moved in with Zhenya – to stay close to the movement and remain in touch with his team. His hiding was carefully planned: curtains drawn, digital and visual traces minimized. Only a few trusted people knew where he was.

Still, Ratushnyi didn’t disappear from the fight. On the contrary – he stayed deeply involved in everything related to the Protasiv Yar campaign. He ran online meetings, coordinated strategy, mapped out next steps. His focus was absolute – this was his world, every day.

Zhenya struggled to keep him hidden – and it quickly became clear it couldn’t go on forever.

That’s how Roma Ratushnyi ended up in Brussels.

* * *

When Peter Wagner, Head of the European Commission’s Support Group for Ukraine, first saw Roma in 2019, his impression was immediate: this young man didn’t look like someone who wore a suit often. Too young. And the tie – probably not his thing either.

What Wagner didn’t know was that Roma had started wearing suits at sixteen – even in the summer heat, even on the barricades of the Maidan.

Brussels first heard of him in December 2019, when the European Endowment for Democracy (EED) announced that a persecuted Ukrainian activist would be arriving to present his case. Ratushnyi already had their trust – and if EED vouched for someone, people listened.

He was composed, focused, and completely convinced of what he was doing. He didn’t talk much.

«He should speak more», sighed Yulia Kononenko. «He’s a future leader – our future.»

People loved assigning labels to Roma. Some even started calling him «our little Chornovil» – a reference to Vyacheslav Chornovil, the Soviet-era Ukrainian dissident and independence leader known for his fearless resistance to authoritarianism.

But what struck Wagner most was Roma’s conviction. In a country that had just come out of a revolution and was already at war, here was a young man who stood up to injustice – for the sake of a single green ravine in his neighborhood.

Wagner considered himself no longer young. In his own youth, he too had defended trees and fought against overdevelopment. But expressing yourself in a Western democracy wasn’t dangerous. You could protest, campaign, criticize – without fearing for your safety.

In Ukraine, what Roma was doing felt more like laying your neck on the guillotine.

Some time later, Wagner posted a photo with Ratushnyi on Twitter, along with a caption:

«Impressed by the courage of Roman Ratushnyi, Yulia Kononenko and many other activists defending Protasiv Yar – a historic green area in Kyiv. Alarmed by reports of threats and attacks against them.»

And then something shifted.

For the first time in months, the cars with unmarked license plates disappeared from outside Roma’s home.

Andriy Smyrnov is the former Deputy Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine (2019–2024). In 2025, he was taken into custody with the option of bail set at 18 million hryvnias. The bail was subsequently paid.Smyrnov was officially charged with money laundering and accepting a bribe in an especially large amount. According to the investigation, he planned to launder the funds through the construction of private houses with a total area exceeding 300 square meters in a recreational zone in the Odesa region.